By: Majken Christensen, astrophysicist

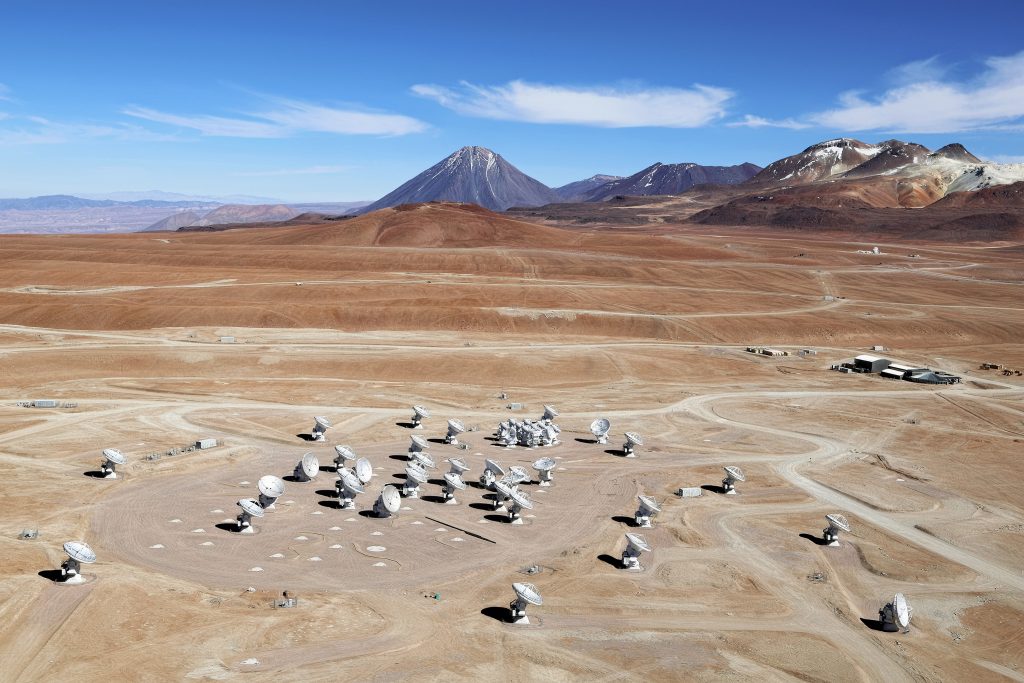

On the mountain tops of the driest desert in the world is an array of antennas pointed at the sky. 66 large antennas are configured to look deep into the regions of space that are not otherwise accessible to regular optical telescopes.

This amazing antenna array is located in the Atacama desert in Northern Chile and operates by detecting radio waves emitted from dust regions in the Milky Way. It is called ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) and behind this super telescope is a whole organization of people that work every day to make it possible not only for researchers to test their theories but also for citizens all over the world to learn about our fantastic universe.

I had the amazing opportunity to go to the Atacama desert in 2010 to work for a few weeks at the neighbor telescope APEX while the ALMA Observatory was still under construction. In the desert was where I met Dr. David Rabanus for the first time. He worked as station manager on the APEX telescope on behalf of the European Southern Observatory.

Today, 8 years later, he works freelance with education development at Alphabetization and he is also is my guest on this second interview at “Science Communication Space”.

From experimental physics in Germany to radio astronomy in Chile

Dr. David Rabanus is German and went to high school in Germany. After his high school exams he continued to study physics at University of Wuppertal, where he got his diploma in experimental physics. At the Technical University of Berlin he graduated on studies he performed at the German Aerospace Centre (DLR).

His academic career path was followed by a 2-year stay at NASA’s Space Science Institute and a post-doctoral position at the University of Cologne, where he worked on submillimeter instrumentation. This would become useful as he became station manager at APEX Observatory in 2007, which is an observatory devoted to observing radio waves in the millimeter and submillimeter region of the electromagnetic spectrum.

In 2011 the ALMA Observatory would function with Dr. Rabanus as Instrument Group manager during the assembly, integration and verification phase of the observatory. This is -so far- the biggest telescope the world has ever seen and Rabanus was in charge of the hardware of the receiving signal controlled by computer systems. He does not hide how he loves to apply scientific concepts and tools to everyday-life problems:

“In the observatory we work on Linux systems (distribution “Scientific Linux”), and mostly the programming is done in the computer language Python. The applications range from controlling the instruments, readout of data, commanding the antennae and receivers etc.”

Working in high altitude challenges human health

Even though a job with computer systems might sound like something you have heard before, the conditions for Rabanus were unlike those at most work places. His office was located in the desert of Atacama and the observatory itself (i.e. the 66 antennas) was located 5 km above sea level. This gives the best conditions for space observations, but it is not entirely without health risks:

“For best possible transparency of the atmosphere at the ALMA frequencies, our observatory is located at a geographic altitude of 5000 m a.s.l. That makes work for humans deployed to this altitude rather difficult.

Scientifically, this is a new window to the universe, as we are now able to zoom in into objects of interest, like exoplanets, and we are able to investigate those exoplanets for their atmospheric compositions, temperatures, and other general properties. I find that amazing.

You need a good physical condition, low amount of overweight, and get accustomed to deep breathing techniques for working at high altitude. The lack of oxygen causes the heart to pound more, and your arterial pressure rises. It shouldn’t exceed a certain threshold in order to keep the risk of blood vessel rupture low.”

Balancing the engineering work at ALMA with science outreach in schools

Working under these extreme conditions in the Andes mountains did not prevent the doctor in physics to continue his work in Chile. In fact, his career at ALMA included several positions:

“After about two years I became one of the Array Maintenance Group managers, together with another colleague in counter shift.

We organized the operations of the hardware of the observatory, which includes proper spare part stock-keeping, hiring of technicians and engineers, in-house training on the technologies used at ALMA, repairs and sub-system swap-out in case of failures, studies of failure-modes and the development of general preventative actions.

The idea is to maximize the number of operational antennas in the ALMA array.”

Cigan

The work at ALMA affects people all over the globe: researchers obtain astronomical observations to use in their research and the general public are provided with knowledge about the universe we live in. Rabanus was active in outreach and science communication also when his work at ALMA was taking up most of his time:

“We did open door days, and I visited a number of primary and secondary schools in Chile for dissemination of the work at the observatories.

There is this nice government initiative in Chile which is called “1000 scientists into 1000 classrooms”: You sign up on a web portal, stating your topic, duration and availability, and some schools will contact you for a talk in the national science week in November.”

The importance of science communication in Chile

These activities are not only time consuming but also require large amounts of personal investments and efforts. Rabanus explains that science communication for him is a very important matter:

“It is paramount to feed back the results of science to the general public, because in most cases science is financed through tax-payers money. Therefore they need to know what’s being achieved with it.”

Rabanus has professional experience from two different continents and that made me curious on how he sees science and science communication being different in South America and Germany/Europe?

“I can only speak for Chile, though, since I lived there for almost 10 years. There, science in general covers a much lesser fraction of the gross product of the country (about a fifth of what is spent in Europe), hence it is just for a small scientific elite.

In science communication I don’t see a difference in the need for it, but I do have the impression that in Chile there is more public interest for it. Maybe, as an emerging society, they appreciate more the scientific progress?”

Follow Dr. David Rabanus

Rabanus moved to Chile in 2007, first in order to work at APEX, then switched to ALMA in 2011. Afterwards he relocated back to Germany in 2016, where he now works with education development for Alphabetization.

You can follow Dr. David Rabanus on Twitter @DavidRabanus.