Insects for dinner? A promising alternative for animal feed

Sofia Christou is currently a science technician at The University of Salford in Manchester, UK, with a passion for exploring novel scientific discoveries that pave the way for a better future. This article draws inspiration from her previous work as a research scientist in the animal feed-additive industry. When she’s not diving into science, you’ll find her blogging about her other great love –Eurovision!

This article is part of the myths, mysteries and misconceptions theme.

edited by mimmu and lotte and illustrated by kenia, sophie, and vicky. Reviewed by Max Yates. Should you have any comments, please let us know!

Imagine a future where farming animals requires significantly less space and water, and produces fewer greenhouse gas emissions. Close your eyes and picture the farm of the future: chickens happily clucking, cows grazing in the distance, and a faint buzz from a nearby insect-rearing facility. On that imaginary farm, animals are thriving on an innovative diet – one that doesn’t rely on soybeans or fishmeal but instead on protein-rich insects.

Why this unusual choice? Our planet faces huge challenges as we strive to feed a growing global population. By 2050, food production needs to increase by 70%, yet our current food production methods are unsustainable. Soybean and fishmeal, the main animal feed sources, come with steep environmental costs: soy farming drives deforestation, greenhouse gas emissions, and heavy pesticide use, while fishmeal production overexploits marine ecosystems.

Insects are good for you: the healthy benefits of insects

Enter insects: nature’s tiny, yet efficient protein factories. Insect production requires far fewer resources and has a minimal environmental impact. Insects are already gaining attention as a sustainable alternative for livestock feed. Let’s dive into the world of insects and their potential as animal feed!

Insects are an attractive alternative source of animal feed because of their nutritional and environmental benefits. They are like tiny superfoods for animals, loaded with proteins, fats, minerals, and vitamins. On top of that, insects are packed with chitin (pronounced ‘kai-tin’), which can make up to 30% of their dry weight. Chitin has been shown to promote animal gut health and boost immunity. This can provide them with a natural boost, working like a secret weapon for their gut health and immunity.

From an environmental perspective, insect farming is sustainable since it’s a space-saving marvel: vertical farming turns even the tiniest patch of land into a towering protein factory. On top of that, unlike traditional agriculture, insect farming doesn’t need pesticides, antibiotics, or growth hormones – it’s a clean, green operation.

Why is this a big deal? Let’s start with antibiotics. Farmers have historically used them not just to treat and prevent disease in livestock but also to promote faster growth. However, regulations have changed; antibiotics can now only be used with veterinary oversight for disease treatment. The EU banned antibiotic growth promoters in 2006, and the Food and Drug Administration followed suit, prohibiting their use for growth promotion in the US. But the concern remains: the overuse of antibiotics has triggered a global problem – antibiotic-resistant bacteria. These so-called ‘superbugs’ are like the villains in a sci-fi movie, evolving faster than we can create new antibiotics. As a consequence, infections that were once easily treated could become life-threatening for humans and animals alike.

Growth hormones, on the other hand, are used in some countries to promote faster weight gain in cattle or boost milk production in dairy cows. However, their use is controversial. Animal welfare advocates raise concerns about potential health impacts on livestock, such as musculoskeletal dysfunction or udder infections, while scientists and consumers debate the safety of hormone residues in food. Some places, like the EU and Canada, have banned their use, while others, like the US, allow them under strict regulations. In short, it’s a complex issue that sparks debate over the sustainability and safety of modern farming practices.

And pesticides? They might keep pests at bay, but they harm our ecosystems by contaminating soil and water and killing beneficial insects.

Insects, however, don’t need these extras: they grow just fine on their own, thriving in controlled environments without any chemical aids. And the benefits don’t stop there. Insects leave behind valuable by-products that can be further used as organic fertilizers, turning yesterday’s scraps into tomorrow’s fertile soil. With insects on the menu, it’s like the cycle of life gets a turbocharged upgrade!

What’s on the menu? Key insect species

Insects are naturally found in the diets of various animals such as fish, shrimp, chickens, and pigs. However, not all insect species are edible or suitable for farming. An insect is good for farming if it grows fast, reproduces easily, eats cheap food, is safe to raise, and is packed with nutrients. At the moment, the most commonly produced insect species for animal feed are black soldier flies (Hermetia illucens), yellow mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), and house crickets (Acheta domesticus). These insects are fast-growing, adaptable, and easy to care for, making insect farming efficient, sustainable, and scalable.

Black Soldier Flies

Meet the black soldier fly, a quiet hero of the insect world. These remarkable creatures naturally thrive in places like manure piles and organic waste – think coffee bean pulp, veggie scraps, and distillers’ waste. But don’t let their humble hangouts fool you; they are packed with potential.

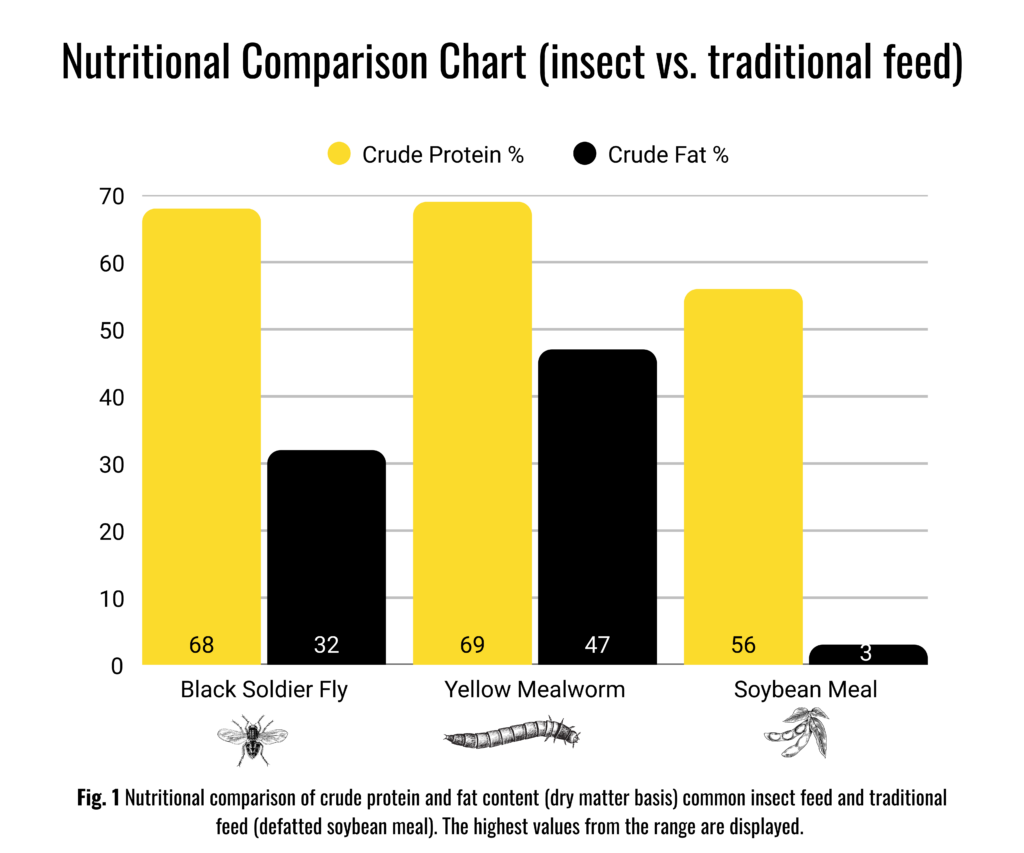

Black soldier fly larvae are nutritional powerhouses. With a similar protein and higher fat content than traditional soybean meal (as illustrated in Figure 1), they’re a supercharged feed option for animals like chickens, pigs, and trout, supporting their growth like a tailored meal plan. Another advantage is that adult black soldier flies are refreshingly low maintenance. They aren’t interested in human habitats and won’t bother you with buzzing or biting – they are all about doing their job and keeping to themselves.

Mealworms

Mealworms are the rising stars of animal feed – especially in poultry. Like black soldier flies, they can be grown on low nutritive waste products, turning scraps into sustenance for boiler chickens and other livestock. Both the protein and fat quantity of the mealworm are higher than traditional soybean meal, making them a superfood for livestock. Plus, they’re not just nutritious – they’re delicious (at least to livestock), making them a top pick for their high palatability.

Crickets

These little jumpers are considered a superfood, being rich in fats, vitamins, minerals, proteins, and other nutrients. Crickets strike the perfect balance between speed, efficiency, and versatility, making them one of the most accessible insects to farm. While the black soldier fly excels at waste management and mealworms are steady performers, crickets stand out for their ease of farming, nutritional value, and adaptability.

Even pigs are hopping on the cricket bandwagon: a study from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences found that pigs thrived on diets containing cricket flour. With such impressive stats, crickets are on track to become star players in the future of feed.

Why are insects not always on the menu? The not-so-sunny side of insect farming

When it comes to making insects a mainstream option for animal feed, the road ahead has its twists and turns. The biggest challenge that comes with insect farming is legislation; each country has its own rules for ensuring animal feed is safe. When it comes to regulations, the EU plays it extra safe, with some of the most restrictive policies around. It wasn’t until 2021 when the EU finally gave the green light for insect-derived processed animal proteins in poultry and pig feed – a giant leap for the industry.

But why are only specific insects allowed on the menu? It’s all about ensuring safety, sustainability, and quality. Right now, the EU has approved a small but mighty lineup of insects as ‘novel foods’: the yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor), migratory locust (Locusta migratoria), house cricket (Acheta domesticus), and lesser mealworm (Alphitobius diaperinus larva). Each of these bugs has passed rigorous checks, proving they’re not just nutritious but also safe for animals and humans.

Then there is the science. Insects may be small, but the gap in research is big. We need more studies on everything from the substrates insects are raised on to allergenic risks and how to make them easier for animals to digest.

And let’s talk money. At present, insect meal is costly. Recent price estimates for insect meal range from 3,800 to 6,000 USD per US ton, which is significantly higher compared to fishmeal, ranging from 1,400 to 1,800 USD per ton between 2020 and 2023. Soybean meal, on the other hand, only costs approximately 500 USD per ton. As a result, the cost of insect meal is not yet competitive, costing three to four times more than fishmeal and up to ten times more than soybean meal. But why are insects so much costlier than conventional feed?

Insect farming requires specialised facilities with controlled temperature, humidity, and light to optimise growth and reproduction, which can be costly to establish and maintain. Scaling up production is no easy task either, with logistical and technological hurdles to overcome. Plus, while insects can munch on organic waste, they still need specific, carefully prepared diets to grow their best, which adds to the price tag.

On the flip side, insect farming offers an exciting opportunity to cut costs in several key areas: it eliminates the need for costly synthetic fertilizers, lowers reliance on fossil fuels, reduces transportation expenses (insect farms thrive right in or near urban centres), and potentially reduces labour costs. It could be a game-changer for sustainability and efficiency!

Finally, there is the ethical side of the story. Insects might not wag their tails or purr, but growing evidence suggests that some species – like flies, crickets and grasshoppers – have cognitive abilities, including learning, memory and decision-making. This raises important questions about their welfare that we’ll need to address as the industry grows.

From science to ethics, the journey to insect-fed farms is exciting, but there’s a lot of work to do before it becomes the norm. Nevertheless, many innovative businesses are already focusing on insect farming.

Insects in the market: the buzz about bug businesses

The world of insect farming is crawling with innovation, and several companies specialise in making bugs a staple in animal feed. But how do we help insects reach their full potential and scale up production? Enter the world of bioengineering and selective breeding. Just like farmers have spent centuries refining high-yield crops and fast-growing livestock, insect farmers are now applying the same principles to their tiny livestock. Selective breeding involves choosing the ‘best-performing insects’ – those that grow faster, convert waste into protein more efficiently, or have higher nutritional value – and using them to breed the next generation. Over time, this process creates a kind of insect elite, perfectly tailored to the needs of farming. Think of it as matchmaking for bugs, with the goal of creating a super-efficient, high-performing population. Combine that with advances in bioengineering, and we’re talking about insects 2.0 – bugs that are not only sustainable but optimised to help feed the planet.

Take BetaBugs, for example. This Edinburgh-based company is on a mission to create the ultimate black soldier fly. Through genetic improvement, they are essentially designing ‘super flies’ optimised for large-scale production. Across the pond, EnviroFlight in the US produces all-natural sourced black soldier fly larvae for animal feed, pet food, and plants. Their approach focuses on sustainability, turning food waste into protein-packed larvae that are a hit with farmers and pets alike.

At the same time, improving farming technology is crucial. Automated feeding systems, climate-controlled rearing facilities, and advanced monitoring tools are making insect farming more efficient and cost-effective. It’s a team effort between science, technology, and nature to get these tiny protein factories buzzing at full capacity.

Building a Future with Insects

The successful implementation of insects as an alternative feed source requires close collaboration between the government, academia, and industry. Think of it as a potluck where the government brings the rules (aka legislation and standardisation), academia stirs in their knowledge on biology and environmental science, and the industry serves up innovative and sustainable farming practices. Together they can cook up a future where insects are a viable, eco-friendly option for livestock feed.

This interdisciplinary approach isn’t just about feeding animals – it’s about feeding the planet in a way that’s sustainable for generations to come.

So, here’s to insects: the small but mighty heroes of a greener, more sustainable future!

References

Atta, A.H., Atta, S.A., Nasr, S.M. et al. (2022). Current perspective on veterinary drug and chemical residues in food of animal origin. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29, 15282–15302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-18239-y

Biteau, C., et al. (2024). Insect-based livestock feeds are unlikely to become economically viable in the near future. Food and Humanity, 3, 100383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foohum.2024.100383

FAO (2021). Looking at edible insects from a food safety perspective: Challenges and opportunities for the sector. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4094en

International Platform of Insects for Food and Feed (IPIFF) (n.d.). Insects as Novel Food: EU Legislation. Available at: https://ipiff.org/insects-novel-food-eu-legislation-2/#question1 [Accessed 2 January 2025].

Jeong, S.H., Kang, D., Lim, M.W., Kang, C.S., Sung, H.J. (2010). Risk assessment of growth hormones and antimicrobial residues in meat. Toxicological Research, 26(4), 301-313. https://doi.org/10.5487/TR.2010.26.4.301

Kasri, K., & Purwanti, S. (2021). Mealworm as an alternative protein source: Potential for the processing of fish meal and soybean meal replacement feed on broiler performance. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 788(1), 012079. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/788/1/012079

Lambert, H., Elwin, A., & D’Cruze, N.D. (2021). Wouldn’t hurt a fly? A review of insect cognition and sentience in relation to their use as food and feed. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 243, 105432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105432

Lee, C.G., Da Silva, C.A., Lee, J.Y., Hartl, D., Elias, J.A. (2008). Chitin regulation of immune responses: An old molecule with new roles. Current Opinion in Immunology, 20(6), 684-689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2008.10.002

Malematja, E., Manyelo, T., Sebola, N., & Mabelebele, M. (2023). The role of insects in promoting the health and gut status of poultry. Comparative Clinical Pathology, 32, 501–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00580-023-03447-4

Miech, P., Lindberg, J.E., Berggren, Å., Chhay, T., & Jansson, A. (2017). Apparent faecal digestibility and nitrogen retention in piglets fed whole and peeled Cambodian field cricket meal. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 3(4), 279-288. https://doi.org/10.3920/JIFF2017.0019

Orkusz, A. (2021). Edible insects versus meat – Nutritional comparison: Knowledge of their composition is the key to good health. Nutrients, 13(4), 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041207

Soil Association (n.d.). Reducing antibiotics in farming. Available at: https://www.soilassociation.org/causes-campaigns/reducing-antibiotics-in-farming/ [Accessed 2 January 2025].

The Poultry Site (n.d.). Insects as animal feeds. Available at: https://www.thepoultrysite.com/articles/insects-as-animal-feeds [Accessed 2 January 2025].

Wang, X. (2022). Managing land carrying capacity: Key to achieving sustainable production systems for food security. Land, 11(4), 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11040484

Wang, Y.-S., & Shelomi, M. (2017). Review of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) as animal feed and human food. Foods, 6(91). https://doi.org/10.3390/foods6100091