Part 1. The train

I was on my way from Moscow to my hometown Voronezh in the center of the European part of Russia, when I heard something very unusual for an intercity train in Russia: people talking in English. I was even more surprised when it turned out that those two mysterious English-speaking ladies were sharing a compartment with me. Naturally, I became curious where they were headed and why they spoke English to each other although both had a slight, but well recognizable German accent. Those two ladies were Elske Rosenfeld from Germany and Åsa Sonjasdotter from Sweden, now both living in Berlin.

“What are you guys doing here in Russia?“, I asked

“We are artists. We are on our way to a workshop to present our research project“, they replied

“Artists… research project?! I should probably pay this workshop a visit”, I thought.

Part 2. Artistic research

Artistic research is currently a developing field. The Stockholm University of Dance and Circus defines it this way: “Artistic research is to investigate and test with the purpose of gaining knowledge within and for artistic disciplines. It is based on artistic practices, methods, and criticality.” [1]

Additionally, one can think of artistic research as a strategy in art that adopts research methodology of science.

“These days, the borders between different fields and concepts are becoming more and more flexible and blurred. These changes give science and art a platform to penetrate each other and create common areas of interest, adopting each others’ methods and forms. While scientific research has a very well defined methodology, forms, criteria and terminology, artistic research is more like an open platform for various approaches.” – Yana Malinovskaya, an artistic researcher [2]

Part 3. Divnogorie

The workshop Åsa and Elske were traveling to was held in Divnogorie, a very special place in the centre of the European part of Russia. Divnogorie is a national park with a unique landscape and a local history museum. But it is also home to more than 2000 people who live in a small village in the park.

That half-day workshop was entitled, “New Questions in Modern Practices of Kraevedenie”. The Russian word “kraevedenie” can be translated as the “science of places”. Practitioners of kraevedenie investigate local areas, the cultural and social aspects of local communities and the interaction between human society and the environment. As a research discipline, kraevedenie was developed by autonomous groups of amateur scientists in the early 20th century. It was a center of a popular social movement after the revolution of 1917 until the 1930’s , when it reduced in significance as a consequence of the Soviet Union’s ideology of forced cultural unification; there was no room anymore for highlighting the cultural differences between the various local communities of a newly-formed country.

The purpose of the workshop in Divnogorie was to discuss how already-forgotten practices of kraevedenie can nowadays be used in artistic research. Artists, historians, scientists, students of the local university (my alma mater) and local villagers were brought together to discuss the uniqueness of Divnogorie and its local community, from an artistic point of view.

Art, when it uses scientific methods, can be a very powerful tool to raise questions which are important to society

One of the main things I came to realize during this workshop is that art, when it uses scientific methods, can be a very powerful tool to raise questions which are important to society. Take, for example, Divnogorie, a unique isolated place, which has been home for many centuries to tribes and communities of people who are extremely attached to the unique landscape which surrounds them. These isolated villagers might not identify with the history books that describe the times they have been living in. In a sense, there might be no room for the stories of local communities within official accounts of history.

For the past three years, a director of Divnogorie museum, Marina Lylova, and her team have been providing a platform for a group of artists to run a number of projects revolving around the history and nature of the place. Marina Lylova is sure that art practices can help to raise the awareness of the local history of Divnogorie:

“As a museum, we are restricted by the official accounts of history and politics. In order to work around such constraints and reveal history through the perspective of the private lives of the local people, it is quite important for our museum to get involved in various art and social projects and so provide the museum with an approach to presenting local history as well.“

art projects that were presented in the workshop in Divnogorie:

Radio “Voice of Divnogorie”

by Tatiana Danilevskaya

“… is a micro radio project and series of programs connecting various co-existing in the same area groups of people – inhabitants of the village, the museum-reserve staff, artists of the residence – in audio space”

“Parallel Diagonals: artistic inquiry into a landscape”

a book by Mikhail Lylov

The book (mostly in Russian) sums up the artistic projects that have been running in Divnogorie for the previous years and the artistic research methodologies in general.

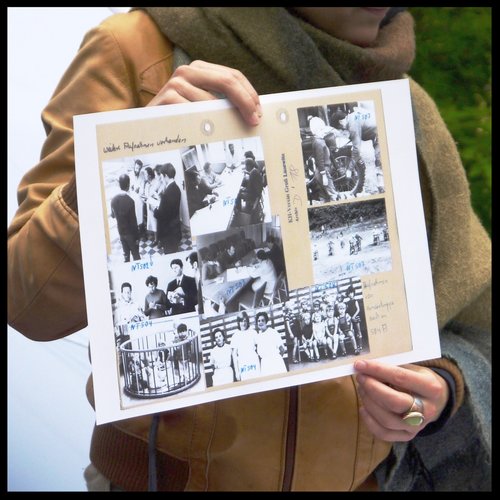

“Adretta: a potato from the GDR travels to Russia”

by Åsa Sonjasdotter and Elske Rosenfeld

This is an ongoing investigation of the two photo archives from the former East German Plant Breeding Institute.

Part 4. Scientific and artistic research. What is the difference?

Artistic and scientific fields of research intersect these days. Both use observations, metaphors, comparisons and create their own methodology and rhetorics; they require serious investigation, literature research, the development and testing of your own hypotheses and challenging opinions of other researchers (or artists). [3]

For my PhD research, I am studying the physics of materials. My research projects always start the same: with a research question. What happens to certain materials under certain conditions? What happens on the initially smooth surface of copper plates under extremely high electric fields at the nanoscale? In the end, my scientific investigation should produce a solid and bold piece (pieces if I’m lucky) of knowledge. Do artists have the same investigation process and what is the outcome they expect?

I asked this question to my new friend Elske Rosenfeld, who also holds a PhD-in-Practise degree and a DOC-Fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences:

“I think this is something everybody would answer differently. There is no protocol of artistic research as there is in science. My methods overlap a lot with academic disciplines like history, anthropology and social sciences, where you look at archives, interview people, read books etc. The end result of my work always depends on a) the material and b) what I want to do with the material. In a way, material generates the outcome of my research. What makes it different from the scientific approach is that I spend a lot of time thinking about and experimenting with how this outcome demands a specific form. “

The purpose of art is surely different from science. During the panel discussion, I asked Mikhail Lylov, an organizer of the workshop, what, in his opinion, is the difference between the goals of scientific and artistic research. If the goal of science is to create a piece of definite knowledge, what then is the goal of the artistic research?

Divnogorie, 2017. pic. by Ekaterina Baibuz

“Both science and art work with problems, but have different goals. Definitive knowledge, which is the goal of scientific research, would be a dangerous notion in art. Art creates pluralistic objects that allow for various responses to coexist for at least some time. That is why, I think, the goal of artistic research is to obtain a temporal consistency of such pluralities. The best art is always a bit uncertain, but in a beautiful way, because it opens the possibility for returning and reinterpretation but that is true for science as well. But for science, it is more robust: it is absolute truth unless it’s disproved by somebody else.”

Part 5. Personal thoughts

Meeting Elske and Åsa, having a conversation with them and attending that workshop opened up new dimensions of thinking to me. I didn’t get many answers, but a lot of questions have been raised in my mind. If science penetrates into art, do artistic methods and ways of thinking penetrate into science? Do artistic and scientific fields of research intersect?

As a physicist I tend to think in terms of numbers, objective knowledge and strict definitions. Thus, it is hard to imagine that research can lead to “various responses coexisting at the same time “. In the end, the purpose of my own PhD research is to explain why nature works the way it does and create a piece of knowledge. But is the knowledge I create an absolute truth? Or is it going to be contradicted in the future, perhaps even by myself? Then the knowledge I create is just a temporary state of thinking. Isn’t such a state what artistic research produces?

Let me know in the comments, what you think about the interaction between science and art.

Sincerely yours,

MSc. Ekaterina Baibuz for A Young Scientist’s Notebook

References

Learn more about artistic research in a performance by Sergio Castiogion for The Science Basement’s Night Of The Arts 2017

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Research#Artistic_research

[2] From the Article “The supervisor-artist relationships in research projects” by Yana Malinovskaya (Яна Малиновская “Куратор и художник в исследовательском проекте”) translated from Russian by E. Baibuz

[3] Tatyana Danilevskaya on artistic research

Photo credits: Ekaterina Baibuz