At the Intersection of Sex and Gender: Differences of Sex Development

Laura Danti is a stem cell researcher with a background in Biomedical Sciences. She is doing her PhD at the University of Helsinki and Karolinska Institutet where she focuses on early ovarian development.

This article is part of the intersections theme.

edited by Kenia & heini, reviewed by Jaakko leinonen, illustrated by sophie hoetzel, read by Emmi olkkonen.

One of the first major decisions about your life is made even before your birth: a gender is assigned based on the corresponding biological sex so that female babies are girls and male babies are boys. Consequently, upon birth, you get brought up according to the societal norms and gender roles associated with being a boy or a girl. It seems rather simple, right? But what about the children who do not neatly fit in those boxes? While assigning a gender to the corresponding sex seems straightforward, things are not always as easy. Welcome to the world of differences of sex development, also known as DSD.

An introduction to DSD and the three types of sex

‘Differences of sex development’ (DSD) are inborn disorders that involve atypical development of anatomical, gonadal and/or chromosomal sex.

Anatomical sex refers to the penis for males and vulva for females. That is, the genitalia or external sex organs that are generally used to visually identify an individual’s sex. Gonadal sex, in turn, refers to the gonads, which are the internal reproductive organs – the testes for males and ovaries for females. Lastly, there is chromosomal sex, which is determined by the sex chromosomes. Chromosomal sex is the genetic composition that, in most cases, determines gonadal and anatomical sex. Females generally are genetically composed of two X-chromosomes (XX), while males have one X-chromosome and one Y-chromosome (XY).

In most circumstances, there is an alignment between anatomical, gonadal, and chromosomal sex. A person carrying XX sex chromosomes will have ovaries and a vulva. In DSD, however, there is a mismatch between the outward appearance of the genitals, the gonads, and the chromosomal make-up of an individual. For example, a baby can be born with XX sex chromosomes and thus be genetically female but still present male or ambiguous genitalia (genitalia that do not look typically male or female).

Depending on the definitions used and the populations studied, estimates about individuals with DSD go from approximately 1 in 20 000 to 1 in 200 of the population. Why the big range? DSD encompasses a diverse group of disorders, making it difficult to accurately estimate prevalence. Moreover, most individuals born with intersex traits present typically male or female genitalia, resulting in an assignment of male or female sex at birth. Many of these individuals go through childhood without being diagnosed with DSD and will only discover this aspect of their biology in adolescence or adulthood. Some will even go through life without ever receiving a DSD diagnosis.

As a stem cell researcher studying early ovarian development, I’ve come to learn a lot about DSD over the last three years of my Ph.D. However, most of the information I have obtained has always been from a scientific perspective: the different categories of DSD, the disease mechanisms, etc. All in hopes of increasing our understanding of DSD and, in the longer run, helping with DSD-related medical struggles such as infertility. But as I went deeper into my studies, I started to grow an interest in studying DSD from another point of view. Namely, I came to the realisation that DSD is not merely a simple biological problem but also has a lot of social and psychological implications. The aim of this article is to shed light on some of those experiences individuals with DSD go through.

From hermaphroditism to DSD, a bit of history on a changing nomenclature

The earliest term used for DSD was hermaphroditism, with individuals being subdivided into three groups: female pseudo-hermaphrodite, male pseudo-hermaphrodite, and true hermaphrodite. The first two terms, male and female pseudo-hermaphrodite, were typically used when sex organs didn’t match the internal organs (which was considered the ‘true sex’). This would mean that a person may have been identified as female because they had a vulva despite having testes. Or a person may have appeared male on the outside because of the presence of a penis, despite having internal ovaries. The latter term, true hermaphrodite, was used instead when a person presented both ovarian and testicular tissue.

After centuries of using the term ‘hermaphrodite’ ‘intersex’ was adopted at the end of the twentieth century in pursuit of a more neutral descriptor. But issues soon started to emerge. The term was quickly appropriated by activists and used as a gender identity rather than a diagnosis or medical condition. The term was also used for a wide variety of conditions, which led to the discussion and criticism as to which people could be described by the term ‘intersex’. Moreover, many parents of children with DSD and many clinicians argued that the term ‘intersex’ was stigmatizing and exclusionary. They argued that it excluded individuals for whom gender assignments at birth were considered unambiguous or who underwent early genital surgeries and would then not identify with the term ‘intersex’. Thus, in the 1990s, ‘intersex’ also fell out of grace, and the need for new nomenclature arose again.

Next, the term ‘disorders of sex development’ was introduced in 2006, but its use was short-lived. Individuals with DSD felt that it pathologized their bodies and themselves, seeing the condition as something needing to be corrected. This reinforced the stigma and shame associated with DSD in the past.

Nowadays, the word ‘disorders’ has been substituted with ‘differences’ and terms such as ‘hermaphroditism’, ‘intersex’ or ‘disorders of sex development’ are no longer used due to their offensive character.

The science behind DSD

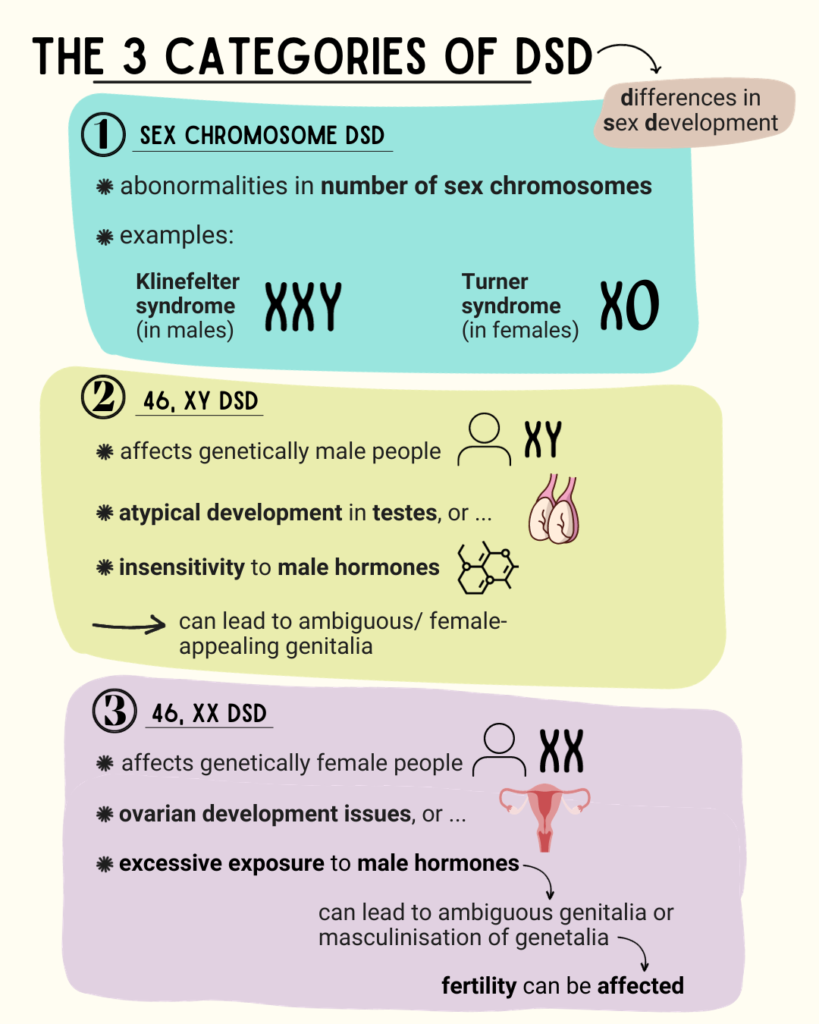

As mentioned previously, DSD can be caused by either atypical development of anatomical, gonadal or chromosomal sex. Therefore, DSD can be divided into three categories: sex chromosome DSD, 46,XY DSD and 46,XX DSD. The first one refers to DSDs caused by abnormalities in the number of sex chromosomes. For example, Turner syndrome occurs when a woman is missing one X-chromosome (X0), and Klinefelter syndrome occurs when a man has an extra X-chromosome (XXY).

46,XY DSDs affect people who are genetically male (XY chromosome) but have atypical development in their testes or are insensitive to male hormones. This can lead to ambiguous or female-appearing genitalia despite having a male XY genotype.

Lastly, we have 46,XX DSDs, which affect individuals who are genetically female (XX chromosome) but might have had, among others, issues with their ovarian development or excessive exposure to male hormones. This can cause ambiguous genitalia at birth or masculinisation of genitalia during puberty. Usually, the development of the ovaries in these individuals is not impaired, but their fertility can still be affected.

On sex and gender, and why they are not the same thing

Before we continue on DSD and how sex and gender are assigned after birth, a small, but important, disgression. ‘Sex’ and ‘gender’ are terms often used interchangeably by society at large, but in fact do not mean the same thing. ’Sex’ refers to biological traits observed at birth based on anatomy and genetics – namely sex chromosomes (genetic make-up) and outward appearance of genitalia and gonads (testes and ovaries). On the other hand, ‘gender’ is a more multidimensional and fluid concept encompassing cultural norms and societal constructs surrounding masculinity and femininity. This means that gender is also uniquely human and is a continuum rather than a binary.

The separation between ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ is vital because a person may be biologically classified as male or female, yet they may identify psychologically as woman, man, non-binary, or gender fluid and therefore connect with the cultural norms of that gender identity. Thus, for example, a person with XY sex chromosomes, external male genitalia, and testes (sex) does not necessarily have to identify as a man but can identify as a woman, non-binary, or gender fluid (gender).

DSD and gender identity

So, how are sex and gender identity established for people born with DSD? The answer is not clear-cut. Historically, gender was usually assigned at birth by the medical team and family based on the apparent genitals. In infants with ambiguous genitalia, the clinician would determine the sex dependent on which genitalia were considered most functional and were thought to give the child the best shot at a normal life. This was followed by extensive early interventions to ensure the sex and gender of the child would conform to the decision, such as sex reassignment surgeries and lifelong hormone therapies.

These early surgical procedures were mostly performed with an outlook to reduce parental psychological distress, with less consideration of the invasiveness of the process to the child and possible long-term harm.

Genital surgery in infancy is now seen as very controversial as it essentially relies on a binary gender classification system. In other words, it is rooted in the belief that for a child to develop a healthy gender identity, it should have ‘unambiguous genitalia’. It is very difficult to predict the future psychosexual characteristics that an individual will develop at birth, even for people with ‘normal’ genitalia. Consequently, this binary classification system has been subjected to bioethical criticism as very limited data is available to support early genital surgery in terms of the physical and psychosocial wellbeing of the individual with DSD. Moreover, this gender-assigning approach is very simplistic and does not always work, as the child with DSD might experience gender dysphoria and change their gender identity as they go through adolescence.

Gender dysphoria is defined as the discrepancy between a person’s assigned sex and the gender they identify with, and the prevalence among individuals with differences in sex development ranges from 8.5 to 20% depending on the type of DSD. Gender identity is influenced by interactions between pre- and postnatal exposure to endocrine factors (such as hormones), chromosomal make-up, and societal factors (postnatal environment and psychosocial experiences). Thus, the concept of gender identity is a complex entity that remains somewhat elusive.

Therefore, careful consideration is necessary when assigning sex and gender to an infant with DSD. One has to consider the type of DSD, societal and cultural factors, the potential biological effects, long-term gender identity, and the ability of the individual to decide their outcome and potential fertility. However, no matter the gender that anyone, especially people with DSD, aligns with, they should get adequate support and healthcare to transition to the gender they identify with.

Lifting the veil

Since the 1990s, there has been a recognised need to approach determining gender identity in a less prejudicing and stigmatising manner and to reduce the likelihood of forced or premature surgical interventions on infants and children with differences in sex development. Since then, emphasis has been placed on family and patient-centred care and advocation for self-determination and bodily integrity for individuals with DSD. Ideally, a multidisciplinary team should be present to support the individual with DSD and their family. The team should consist of a gynaecologist, an urologist, an endocrinologist, a psychologist, a biochemist, a geneticist, and social workers. DSD, however, is a very rare disorder and there is a lack of specialists with the necessary knowledge and skills, which makes multidisciplinary care very difficult.

There is a need for us to take a new look at how we deal with DSD as well and evolve from the mechanical gender assignment of the past. A lot remains to be learned, but if nothing else, I hope this article has lifted at least a tip of the veil that rests on DSD and the crossroads of sex and gender identity. Understanding the science and individuals behind the label can help to create better care and a less prejudiced society for all.

references

- Baxter RM, Vilain E. Translational genetics for diagnosis of human disorders of sex development. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2013;14:371–92.

- National Academies of Sciences E, Education D of B and SS and, Statistics C on N, Committee on Measuring Sex GI, Becker T, Chin M, et al. Measuring Intersex/DSD Populations. In: Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation [Internet]. National Academies Press (US); 2022 [cited 2023 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK581039/

- García-Acero M, Moreno O, Suárez F, Rojas A. Disorders of Sexual Development: Current Status and Progress in the Diagnostic Approach. Curr Urol. 2020 Jan;13(4):169–78.

- Feder EK, Karkazis K. What’s in a Name? The Controversy over “Disorders of Sex Development.” The Hastings Center Report. 2008;38(5):33–6.

- The Global Library of Women’s Medicine [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 4]. Differences of Sex Development | Article | GLOWM. Available from: http://www.glowm.com/article/heading/vol-2–adolescent-gynecology–differences-of-sex-development-intersex-care/id/418293

- Gomes NL, Chetty T, Jorgensen A, Mitchell RT. Disorders of Sex Development—Novel Regulators, Impacts on Fertility, and Options for Fertility Preservation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Mar 26;21(7):2282.

- Witchel SF. DISORDERS OF SEX DEVELOPMENT. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Apr;48:90–102.

- Domenice S, Batista RL, Ivo J PA, Sircili MH, Costa EMF, Mendonca BB. 46,XY Differences of Sexual Development [Internet]. Endotext [Internet]. MDText.com, Inc.; 2022 [cited 2023 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279170/

- Alkhzouz C, Bucerzan S, Miclaus M, Mirea AM, Miclea D. 46,XX DSD: Developmental, Clinical and Genetic Aspects. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 Jul 30;11(8):1379.

- Krieger N. Genders, sexes, and health: what are the connections—and why does it matter? International Journal of Epidemiology. 2003 Aug;32(4):652–7.

- Babu R, Shah U. Gender identity disorder (GID) in adolescents and adults with differences of sex development (DSD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 2021 Feb 1;17(1):39–47.

- Furtado PS, Moraes F, Lago R, Barros LO, Toralles MB, Barroso U. Gender dysphoria associated with disorders of sex development. Nat Rev Urol. 2012 Nov;9(11):620–7.

- Ravendran K, Deans R. The Psychosocial Impact of Disorders of Sexual Development.