A CONVERSATION WITH MASSIMIANO BUCCHI

COMMUNICATING SCIENCE

On May 16, The Science Basement had the chance to interview Massimiano Bucchi to discuss topics related to science communication.

He is a Professor of Science Communication at the University of Trento and editor of the international journal Public Understanding of Science. He has also been a very prolific writer during his career.

How can we get researchers more involved in science communication?

We shouldn’t expect all scientists to get personally involved in science communication. Not all researchers may feel comfortable communicating their findings first-handedly and forcing them to do so might have more negative effects than positive ones. However, we should try to change the obsolete perception that a researcher that is involved in science communication is less accomplished or is even wasting her/his time. Instead, science communication efforts should be valued by research institutions as part of their overall mission.

More than trying to convince single scientists to get involved in science outreach, institutions should equip themselves with teams of people that can be in charge of coordinating science communication initiatives, and that will support researchers in popularizing the findings produced by each university.

How to estimate the quality of science communication?

How to estimate the quality of science communication?

Assessing the quality of science communication is a complex issue. A very important quality factor is scientific accuracy: even though explained in simpler terms, the science presented has to be rigorous. But this is not enough. We should also look at the impact on audiences, which can be at different levels. Unfortunately, not many public engagement initiatives are rigorously evaluated.

Which are the required skills for researchers who want to become science communicators?

Researchers have the advantage that they can already speak the language of science, but they also need to understand society and different audiences. Researchers interested in communicating findings from a specific field (e.g. life science) should also familiarize themselves with the laws regulating research in that field. Finally, they should be knowledgeable not only of the ethics of science but also of the ethics of science communication.

What do you think is the best format to communicate science today?

We tried to investigate whether there is one communication format (e.g. public talks, blogs, podcast, events) that is better suited for sharing research results with the public, but we didn’t observe any prevalence in the effectiveness of a medium over others. What we realized is that the choice of format should always take into account the subject you are communicating and the audience you are communicating it to.

Is society’s trust in science really broken?

This is what we tend to think but, according to recent studies, this it not the case. The majority of people do trust science. What is in crisis is the relationship between science and politics. On the one hand, more and more often, political leaders think they can question the authority of scientific experts or even do without their expertise.

On the other hand, there is growing distrust in politics by scientists. As several trends reveal (Marches of scientists, the movement “314 Action” that has recently led many scientists to run as candidates and some of them to be elected during the recent US midterm elections), the scientific world trust less and less the capacity of politics to take informed decisions.

What is your new book about?

My latest book (How to win a Nobel prize) explains how the Nobel prize has changed the image of scientists in the public eye, mainly through three narratives:

- The genius. Laureates are seen as gifted with a brilliant intellect and incredible creativity that led to achieve great discoveries and ultimately win the Nobel.

- The national hero. People tend to remember especially Nobel prize winners from their own country and, like winners of the Olympic Games, these scientists become part of our national pride.

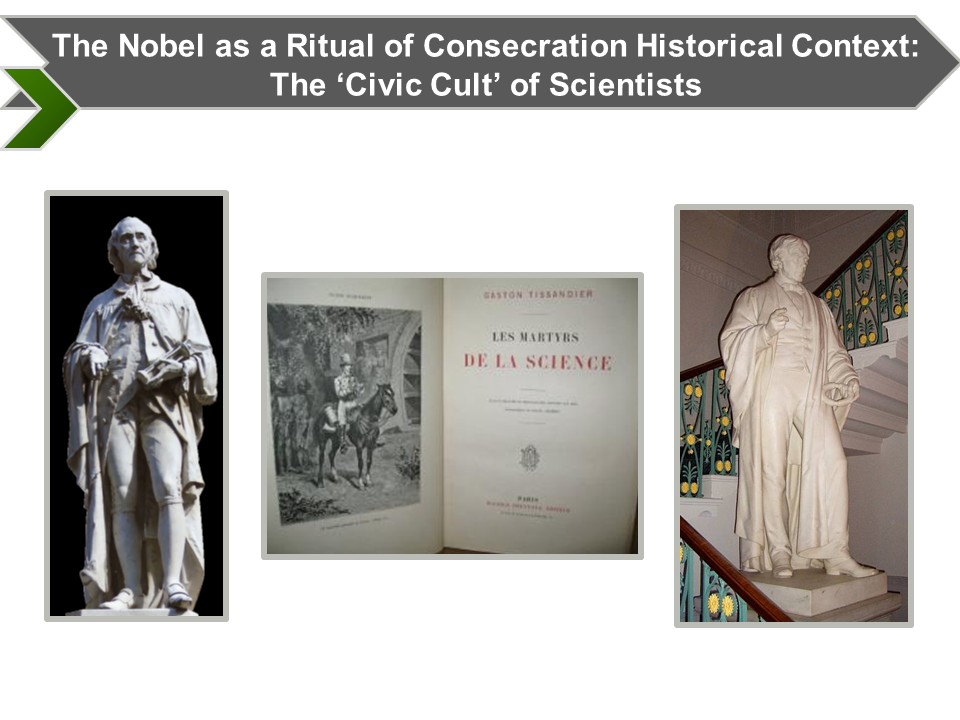

- The saint. A civic cult of scientists developed since the mid-XIX century in strong analogy to the cult of saints. We have statues, figurines, and even relics (like Galileo’s middle finger displayed at Galileo’s museum in Florence).